What It Was Like Inside Tech Startups in Moscow in 1991

...or how Russia lost a generation of tech entrepreneurs then and is doing it again now

When I see stories about all the entrepreneurs and innovators bailing out of Vladimir Putin’s Russia, I think of Stepan Pachikov – and how much Russia lost and the U.S. gained when he got out of the old Soviet Union more than three decades ago.

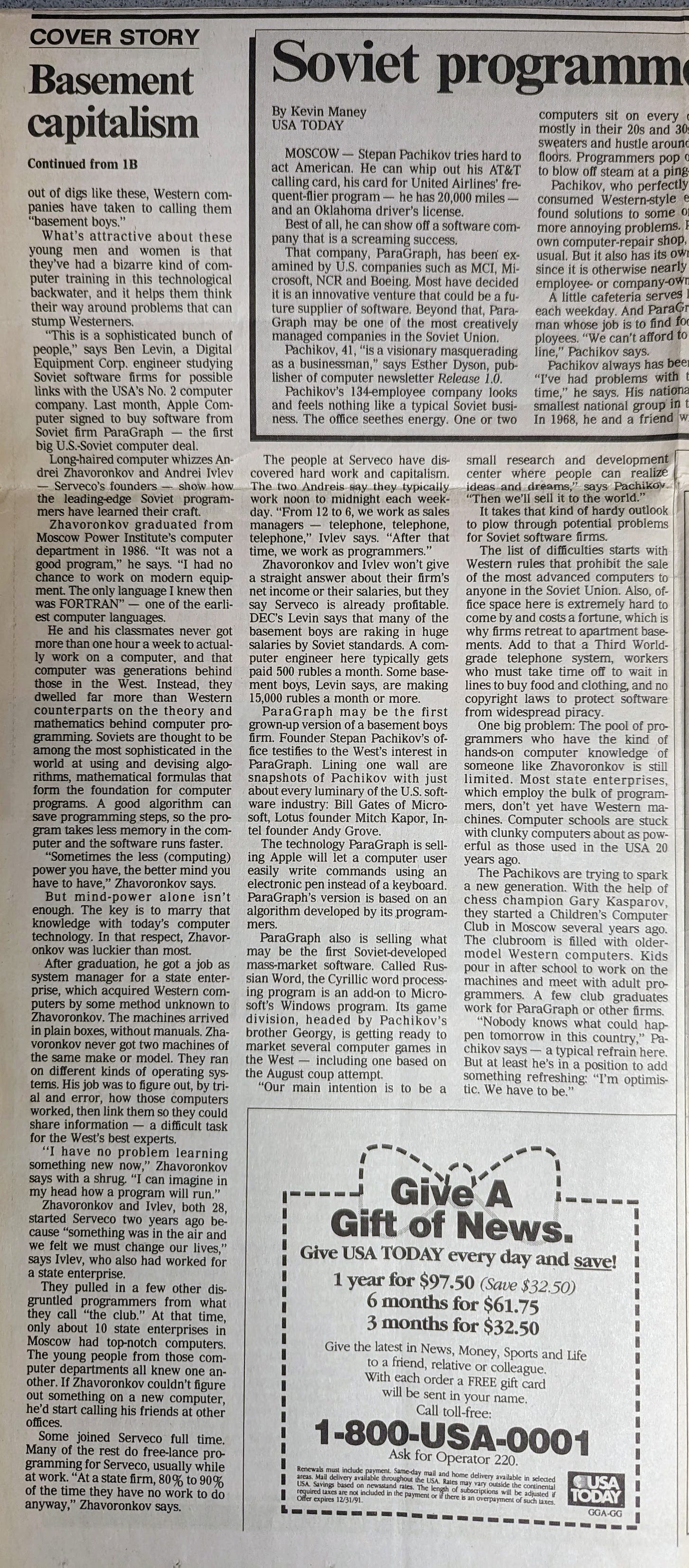

From 1987 to 1993, I covered the business aspect of the disintegration of the Soviet Union. I was always most interested in writing about technology, so I sought out tech stories. During that time, the Soviet Union was slowly opening up, but private businesses were still technically illegal. I wrote about a number of grey-area tech startups in Moscow, most of them operating in some out-of-the-way basement where authorities (or criminals out to steal computers) wouldn’t bother looking.

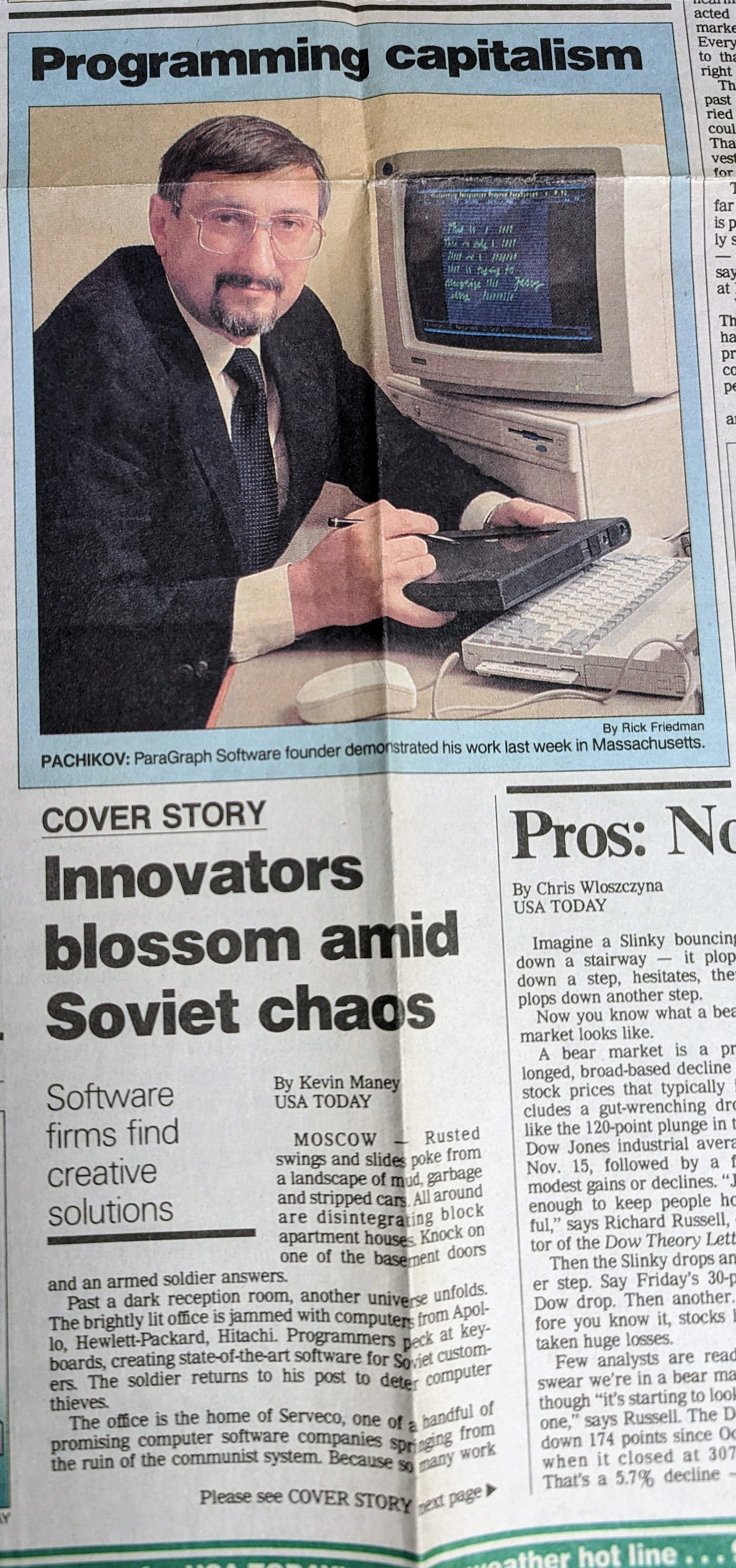

The most successful of these companies was Stepan’s, called ParaGraph. By the time I paid him a visit in mid-1991, he had 134 employees and regularly hosted Americans from companies such as Microsoft and Boeing. One of ParaGraph’s products was software that could recognize handwriting and turn it into digital text – innovative for its time. Apple licensed that software, and it was integral to Apple’s Newton handheld gadget, unveiled in 1993. (Newton was ultimately an embarrassment for Apple, but still…)

I remember how head-spinning it was to walk into ParaGraph. Outside its doors, Moscow was a city at its lowest. This was a time of scarcity, when people lined up for hours to buy food or shoes. Most buildings looked worn out if not falling down. I remember going into the toy section of the giant department store GUM by Red Square, and the few items on the shelves looked like leftovers from the Island of Misfit Toys in the old Rudolph TV special. But when I stepped into ParaGraph, the first thing I saw were piles of cow-pattern boxes from U.S. computer maker Gateway 2000. Inside, the place looked like a Silicon Valley office. It had a cafeteria serving lunch and dinner so employees wouldn’t have to hunt for food, a ping-pong table, and a car repair shop because it was otherwise impossible to get a car fixed.

Stepan seemed to have every intention of becoming a Russian company selling to the West. In the 1991 story I wrote about ParaGraph, he said, “Nobody knows what could happen tomorrow in this country. I’m optimistic. We have to be.”

My story appeared in USA Today in November 1991. The Soviet Union dissolved one month later. But not enough changed for private companies. So Stepan packed up and moved to Silicon Valley, opening a U.S. operation of ParaGraph there. In 1996, ParaGraph spun off its technology that recognized and digitized text in documents into a company called ParaScript, which is still going strong today.

But missing out on ParaGraph and ParaScript is just the beginning of the compounding setbacks Russia suffered by losing Stepan.

In 2000, I attended a large tech conference in Scottsdale, Ariz. Walking down a hall, I heard Stepan call my name. He was sitting on the floor and had his cell phone out. Keep in mind that cell phones at the time were just beginning to have cameras – really bad cameras. Stepan asked me to sit down so he could show me his latest project. He would take a photo of anything with words on it – a document, a sign, a receipt – and it would go to the “cloud” (whatever that was, I believe I thought at the time) where software could recognize the words, tag the item, and store it.

What was he going to call this thing, I asked? Evernote, he told me. And in 2002, Stepan founded Evernote.

Evernote was a hot thing for a while, though it never really lived up to its potential. But it became a sizable global company with a devoted fan base, and was bought last year by Italian tech company Bending Spoons. Stepan stayed on Evernote’s board until the sale was completed.

And still, there’s more to the story of what the U.S. gained and Russia lost with Stepan’s escape.

Stepan has a son, Alex. I first met Alex when he was a teenager playing drums at a jam session at a tech conference he was attending with his father. (I think Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen was on one guitar; super-investor Roger McNamee on another.) Alex worked at Evernote for almost 10 years. In 2016, he co-founded (and is now CEO of) a company called Sunflower Labs. It offers an innovative security system that sends drones out to scout suspicious activity picked up by security cameras on a property. One of Sunflower’s investors is General Catalyst, which I know well: I’ve written three books with GC’s CEO, Hemant Taneja.

It adds up to still-compounding losses for Russia. By being inhospitable to business, it missed out on Stepan’s three world-class tech companies and lost Alex, who might have started a Sunflower Labs in Moscow if things had been different.

And that’s just one person’s legacy. How many other Stepans left Russia back then? How many have left in the past year and will continue to leave? The gross total of Russia’s losses may not be obvious for another decade or two.

I’ve kept in touch with Stepan through the years. Once in a while we meet for lunch. I can’t tell you how many times he’s told me how dangerous Putin is. I sent him an email telling him I was writing this article. This was what he wrote back:

“From 1999, I hated (Boris) Yeltsin for his decision to bring Putin to power. From Feb 2022, I believe that we are at the first phase of WW3, at a similar point to Hitler's invasion of Poland in September 1939.

“All my relatives in my mother's line are in Ukraine, where hundreds of thousands of former Soviets kill every day thousands of former Soviets.

“It is a shame to be a Russian. When I am asked: ‘Where are you from?’ I usually say that I was born in the Caucuses (which is true - I was born in Vartashen, Azerbaijan). My brother still is in Moscow, having a terrible time protecting his business from disappearing … he has dozens of people depending on his ability to protect the jobs. My daughter managed to escape from Russia to Poland and has a job as a columnist in The Insider magazine.

“All of us (my wife, my children, and my friends) believe and hope that Ukraine, with the help of the West, will win the war and Russia will be disintegrated. The genuine concern is the nuclear button which is too close to Putin's finger … I believe that he is crazy and stupid enough … that he is a rat in the corner...”

Here are the original stories I wrote about those early Moscow tech startups and Stepan’s company. These are clips from my files. They’re not available online: