Now that the National Hockey League season is in full swing, we can be thankful that twenty years ago one of the most bizarre experiments in sports television crashed and burned.

No, I’m not talking about Battle of the Network Stars. This is about Fox Sports’ electronic hockey puck and the weird, glowing, comet-tail graphics it produced for the TV screen.

As a columnist for USA Today, I got wind of the concept in March 1995, ahead of most other media outlets. This was long before electronics did much to enhance our sports viewing – before we could instantly see if a pitcher hit the strike zone; before soccer players wore chips that track their movements on the field; before cameras and AI could tell if a tennis shot landed inside the line.

Fox had signed up to start broadcasting NHL games in April 1995 – the first time hockey would be on network television since 1974. Fox was worried that Americans were either too ignorant of hockey or too blind to follow the puck (or both) on a TV screen.

To be fair, 1995 tube TVs were nothing like today’s high-definition TVs. Some TV pictures were so fuzzy, if you had the sound off it could be hard to tell if you were watching Friends or a Congressional hearing. “One of the biggest complaints about hockey on TV is, ‘I can’t see the puck!’” a Fox spokesman, Vince Wladika, told me then.

So Fox started looking at embedding chips in pucks, which would allow computers to superimpose graphics over the puck in order to make it easier to follow. In 1995, Fox was just tinkering. In early 1996, what I called the “compu-puck” was ready. Fox branded it FoxTrax.

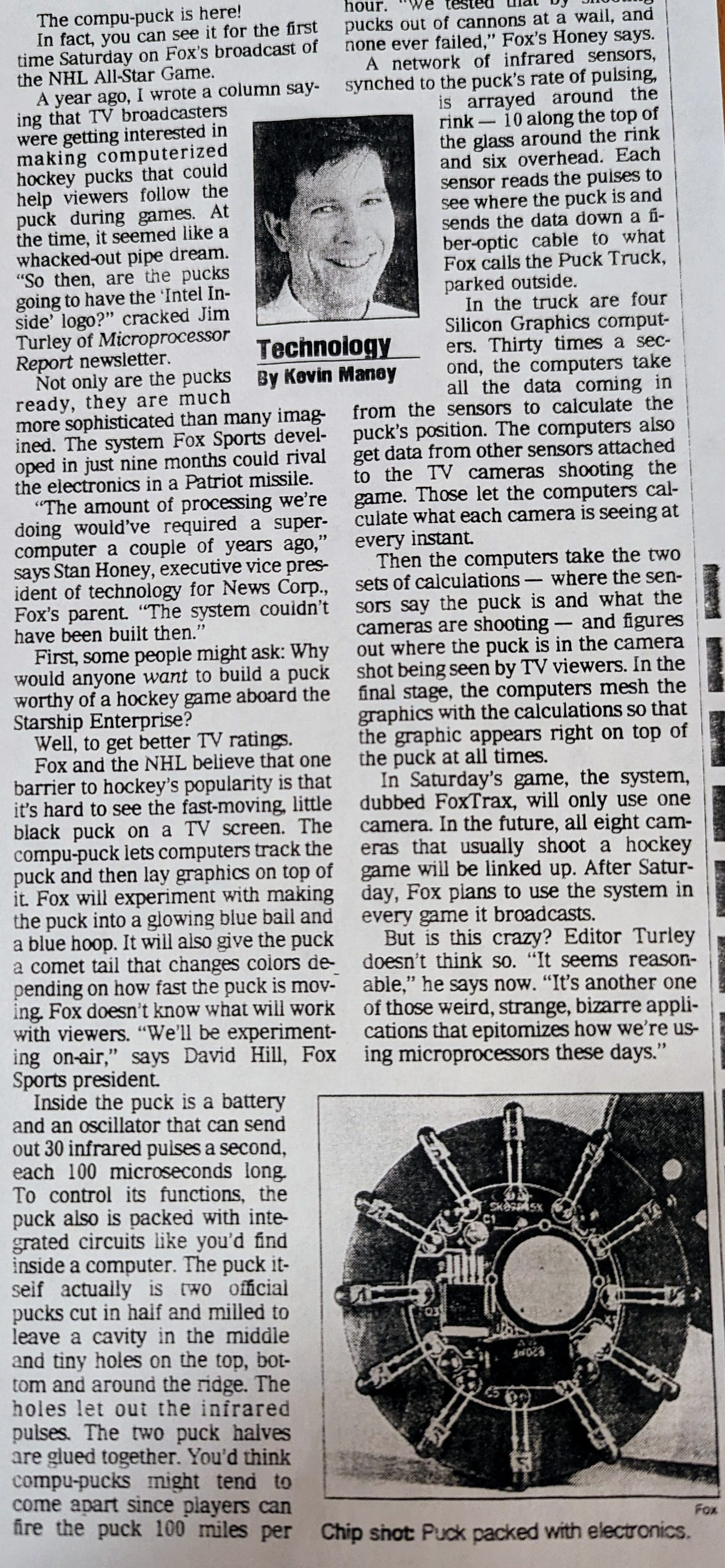

To make it work, Fox cut pucks in half length-wise, scraped out a little cavity in the middle, and inserted a bunch of electronics that could generate 30 infrared pulses a second. Tiny holes around the ridge of the puck let the pulses out. A network of infrared sensors placed around the rink would pick up the pulses and track the puck. The puck had to be glued back together with some kind of super-adhesive. “We tested that by shooting pucks out of cannons at a wall, and none ever failed,” a Fox VP told me.

Old hockey fans will remember what happened next. Fox used the puck-tracking to make the puck glow with a blue halo around it – this was Fox’s answer to helping viewers see the puck better. When a player took a shot, an orange comet tail would swoosh behind the puck.

Neither seemed to do much to pull in new hockey fans, and the hockey faithful thought it was awful. It turned a game into a combination of live action and cartoon – as if a hockey game broke out during the Roger Rabbit movie. Greg Wyshynski, editor of Yahoo Sports’ long dead Puck Daddy blog, once told a journalist: “Imagine if you were watching the Super Bowl and every time the running back disappeared in a pile of tacklers he started glowing like a blueberry from Chernobyl.”

Fox didn’t actually kill off the compu-puck. In 1998, Fox lost the NHL broadcast rights to ABC, and FoxTrax disappeared. ABC apparently didn’t have any similar desires on glowing pucks.

Looking back now, FoxTrax was a victim of the adjacent possible – something that often happens to technology that gets too far ahead of itself. As Steven Johnson explains in his excellent book Where Good Ideas Come From, inventions that take off and are embraced by the masses land in a zone he called the adjacent possible – just a little ahead of what tech can do and a little ahead of what we as humans can adjust to, but not so far ahead that it seems weird or works too poorly. Getting too far ahead of the adjacent possible is what doomed Google’s glasses. General Magic ran into the same problem when it tried to invent the whole internet in 1992, before there really was a consumer internet.

But the adjacent possible always advances as technology gets better and we get comfortable with new inventions. The creators of the compu-puck went on to show how that works. They left Fox and started the company Sportvision, knowing that the basic idea of using electronics to enhance sports viewing would eventually be right. In time, Sportvision created the baseball pitch trackers we now see on every broadcast, the yellow first-down lines on NFL broadcasts, and a bunch of stuff for Olympic events. The company has since been acquired by SMT.

Once high-definition TVs hit the market, the need to artificially enhance the visibility of pucks for NHL games faded away. Instead, technology now can track pucks and players, generating data and probabilities that coaches can use for training and tactics. A couple of NHL teams use virtual reality for training.

But the glowing puck goes on the list of all-time dumb applications of technology, maybe a little behind shoe stores in the 1920s using X-ray machines for fittings.

These are the two columns - in 1995 and 1996 - that I wrote about the electronic puck. Neither are available online.