The Innocence of Early Twitter

The strange tale of a company that didn't know what it was

In early 2009, I sat on a stage in San Francisco with Evan Williams, a co-founder of Twitter, and interviewed him in front of about 300 tech peeps who were curious about this new messaging service that Shaquille O’Neal and Barack Obama were using but that mostly featured anybodies firing off bursts about what they had for breakfast or praising their favorite item from Trader Joe’s.

(Tweet’s from my actual 2007-2008 timeline: Mike Hirshland: “checking rss feeds. and doing dishes.” Jeffrey L. Cohen: “Seeing #ironman.”)

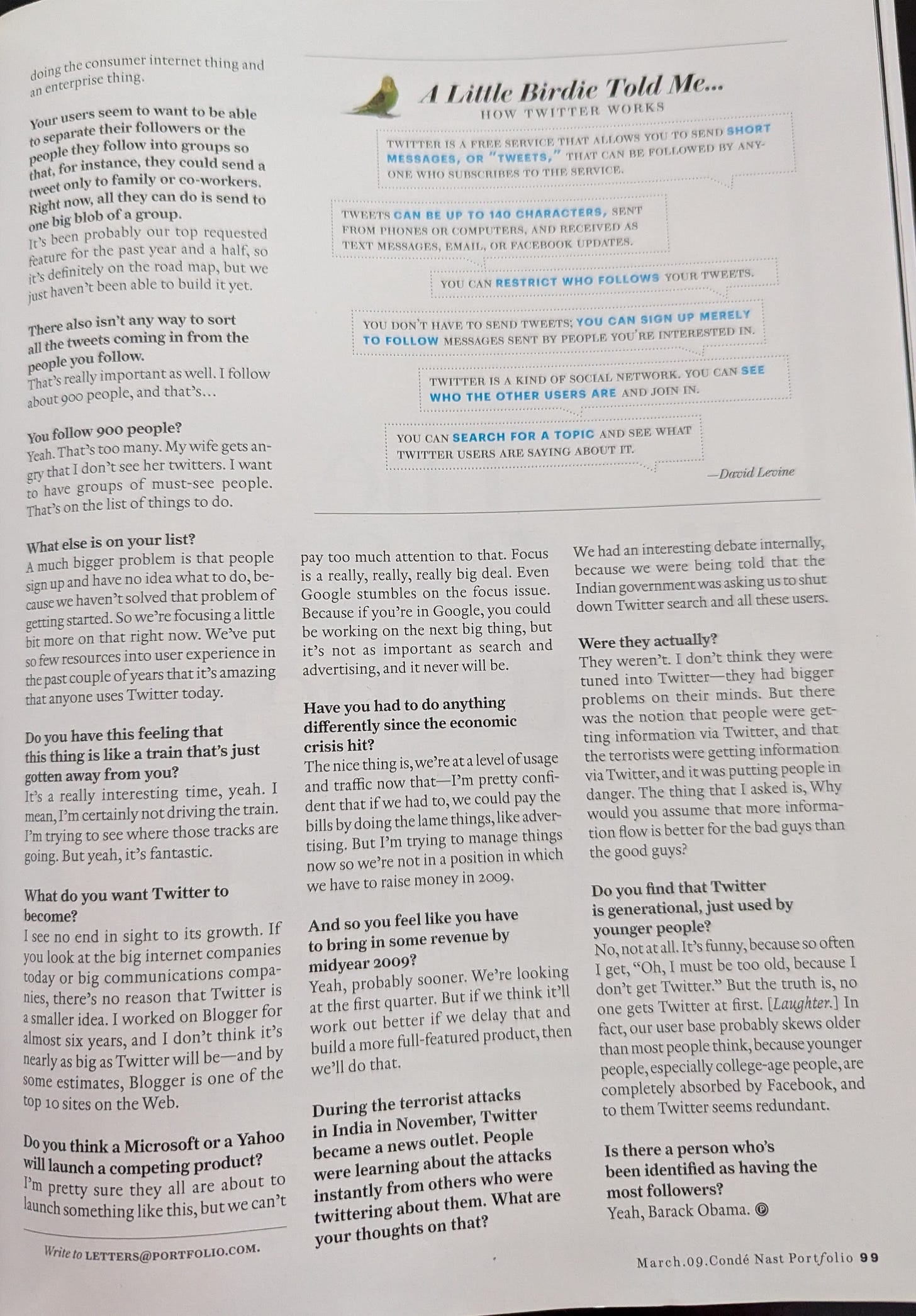

Twitter was so new to most people, when we ran an edited version of the interview in Conde Nast Portfolio magazine (where I was a writer), we had to include a “How Twitter Works” graphic.

Twitter itself didn’t yet know what it was, or why anyone needed it. The company barely knew who was in charge. In 2006, Williams, Jack Dorsey and Biz Stone had all been working on a startup called Odeo, an early podcasting company that Wiliams had founded, Twitter was a side project inside Odeo, built on text messaging – which, on that era’s Nokia and Motorola cell phones with no real screens, was limited to 140 characters.

So, early tweets could only be that long. That was half the fun – finding a way to say something in the length of these last two sentences.

As Twitter started to pile up users, it got spun out of Odeo. Dorsey was its first CEO, lasting two years. Then Williams took charge in 2008, when Twitter had 5 million users. (Stone never got his turn.) Williams told me the company during his tenure employed just 25 people, “and 75 percent are focused on the product and engineering and operations. And we literally have no business people in the company.” Facebook offered to buy Twitter for a reported $500 million. Williams turned down the bid.

The company had no plan for making money. “We will make money,” Williams insisted. “I can’t say exactly how, because we can’t predict exactly what’s going to work.”

Williams was funny and honest and easy to talk to. He mentioned he followed 900 people. To me and the audience, that sounded insane. (Such naive times.) “Yeah, that’s too many,” Williams explained. “My wife gets angry that I don’t see her twitters.” He didn’t call them “tweets” – he called posts “twitters.”

Mostly, Williams came across as still trying to understand what he, Dorsey and Stone had birthed. I’ve rarely run across a tech startup that had so little idea of what it was or where it was going. It solved no pressing problem. I doubt many people sat around in the early 2000s thinking, “Damn, I wish I had a way to send meaningless morsels of information to a lot of people at once.” The founding team released Twitter into the wild and waited to see what people would do with it.

“I’m certainly not driving the train,” Williams said. “I’m trying to see where those tracks are going.”

Around the time Williams and I talked, Apple’s iPhone was changing the smartphone category forever. Screens got bigger and more capable. Phones got real keyboards or keypads. Tweets could get longer and started to be more meaningful – news, promotions, road closures, political messages. Twitter spread globally. Basically, Twitter became the world’s bulletin board. In 2011, it passed 100 million active users a month. A year later, it passed 200 million. In 2013, the company went public on the New York Stock Exchange.

Williams hung on as CEO for two years, 2008 to 2010. Next was Dick Costolo (2010-2105), then Dorsey again (2015-2021), and finally Parag Agrawal 2021-2022).

Of course, most everyone is aware of what happened next. Elon Musk bought Twitter in 2022 for $44 billion. He fired Agrawal and half of the company’s 7,500 employees. In 2023, he renamed it X.

What’s remarkable to me is how innocent and fun Twitter was during Williams’ tenure. In those early days, it could’ve become anything. Over the years, it ended up playing significant roles in history, including events like the Arab Spring and Donald Trump’s rise to political power.

Now, bizarrely, it often seems as if Twitter-slash-X has come full circle, back to not really knowing what it’s good for.

—

This is the interview with Williams as it ran in Portfolio in March 2009. If it’s anywhere online, I can’t find it.

"Williams hung on as CEO for two years, 2008 to 2010. Next was Dick Costolo (2010-2105)"

I believe you meant to say "Dick Costolo (2010-2015)"