The Economy of the Indy 500

Or, that time I hung out with the "poor" drivers at the famous track

The Indianapolis 500 happened over Memorial Day Weekend, as it always does. I didn’t watch it on TV. Apparently, in relative terms, not many people did. Yet the prize money has rocketed through the roof.

This is quite a change from 1988, when I spent time in the racers’ garages at the Indy track and wrote a feature about the business of racing in the 500.

At the time, as my story reported, about 24 million people watched the Indy 500. This year, viewership during the four-hour race peaked at 6.5 million. In 1988, the winner, Rick Mears, got about $810,000 -- $2.2 million when adjusted for inflation. This year’s winner, Josef Newgarden, raked in $4.3 million. So prize money has doubled while the TV audience has shrunk to about one-fourth the size.

But the surprising thing I found out back then about the Indy 500 is that the prize money is barely the point when it comes to the economics of racing. Really, it’s all about being a 200 MPH billboard.

I did most of my reporting on practice day, a few days before the actual race. I had a pass to wander around the garages where the drivers and their crews fine-tune their cars while other cars whizzed by on the track making an enormous noise. I knew little about racing and could barely figure out how to check the oil in my car. Yet it was super cool to see what was going on behind the scenes – which was kind of like what was depicted in the movie Ford vs. Ferrari.

What I hadn’t expected was such a clear socio-economic divide in the pits – something viewers at home don’t see.

I walked over to the area where racing legend Mario Andretti’s team was set up. They had three garages, 25 mechanics in matching outfits, two Lola cars and 10 backup engines.

Not far away was a driver named Phil Krueger. He had one garage, one car, one mechanic, one spare engine and no matching outfits. His team was owned by R. Kent Baker, then a young guy who owned an Indianapolis marketing company called CNC System Sales (which still exists and Baker still runs).

As I talked to Krueger and another shoestring-operations driver named Tony Bettenhausen, I learned that the big gulf between these camps was sponsorships. The Indy 500 has the same kind of economic dynamics that you see everywhere today. Winning cars get more time on camera, which equals more exposure for the brands plastered on the cars – brands like Valvoline, Pennzoil, Pizza Hut and Verizon. Winning drivers also get personal time on camera, where the brand logos on their outfits get seen. So, the brand sponsorship money rolls in for the winners, which gives the winners more money to spend on better cars, engines and mechanics…so they win more and bring in yet more sponsorship dollars. The rich get richer.

And it became obvious why the poor usually stayed poorer. The side of Krueger’s car had a CNC Systems decal because the team couldn’t land any paying sponsor for that spot. Krueger had one other logo on the car — for a trucking company called Taylor Distributing, which, I wrote, “pitched in a few bucks to help.” Other than a tiny Valvoline sticker, that was it.

Bettenhausen’s logos included a nine-store grocery chain and an Oldsmobile dealership. To drum up support and help out his sponsors, Bettenhausen was doing a rush-hour radio show from his garage with a local DJ.

In the decades since, it seems like not much has changed about sponsorships and Indy. Newgarden’s winning car sported a Shell oil company logo and the whole car was decked out in Shell colors – as was his outfit and those of his whole pit crew. The team was a walking Shell ad and Newgarden probably got a fortune for it – in addition to his $4.3 million prize.

In that 1988 race, Krueger, with almost no sponsorship money and a tiny operation, finished an amazing 8th place out of 33 cars in the field. He got $131,053 in prize money for it, and then never raced in the 500 again. He tried to qualify the following two years and failed. Can’t find anything online about what Krueger is doing now.

Mario Andretti, by the way, finished 20th that year. Engine trouble forced him out before the race was over. So, I guess it’s gratifying to know that money doesn’t guarantee a good outcome.

Bettenhausen…well, he finished last. The web says Bettenhausen died in 2014. A friend of his wrote an obit that noted: “He went to sleep in the basement on Sunday afternoon and never woke up when his wife of 50 years, Wavelyn, called him for dinner.”

—

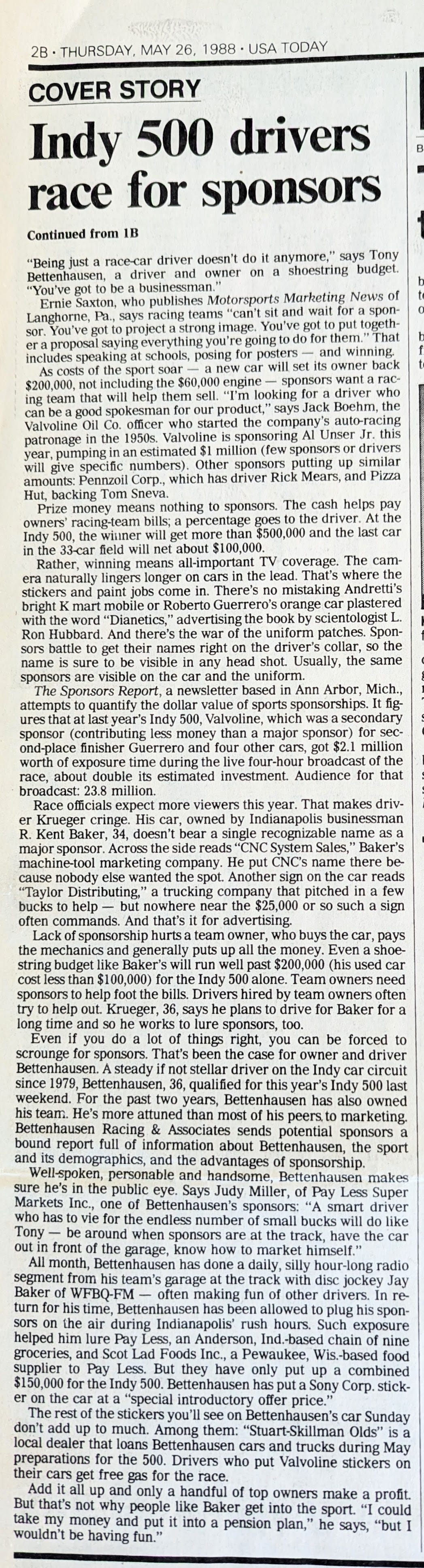

This is the story as it ran in USA Today in 1988. It’s not available online.