I grew up playing hockey, played for my college team, and loved the sport. In the fall of 1985, I had been a business journalist at USA Today for about six months. An editor came to me with an assignment that lit me up like a quart of 5-Hour Energy.

He wanted me to write a feature about the Zamboni company.

Where do I have to travel to, I wondered? Toronto? Halifax? Uh, no, he said. The Zamboni was invented in Los Angeles. The company is based there.

I didn’t see that coming.

Now, when I look back at the story I wrote, I see something else that I couldn’t have understood then: the Zamboni is one of the all-time great stories of a startup creating a new market category, and then dominating it for 75 years.

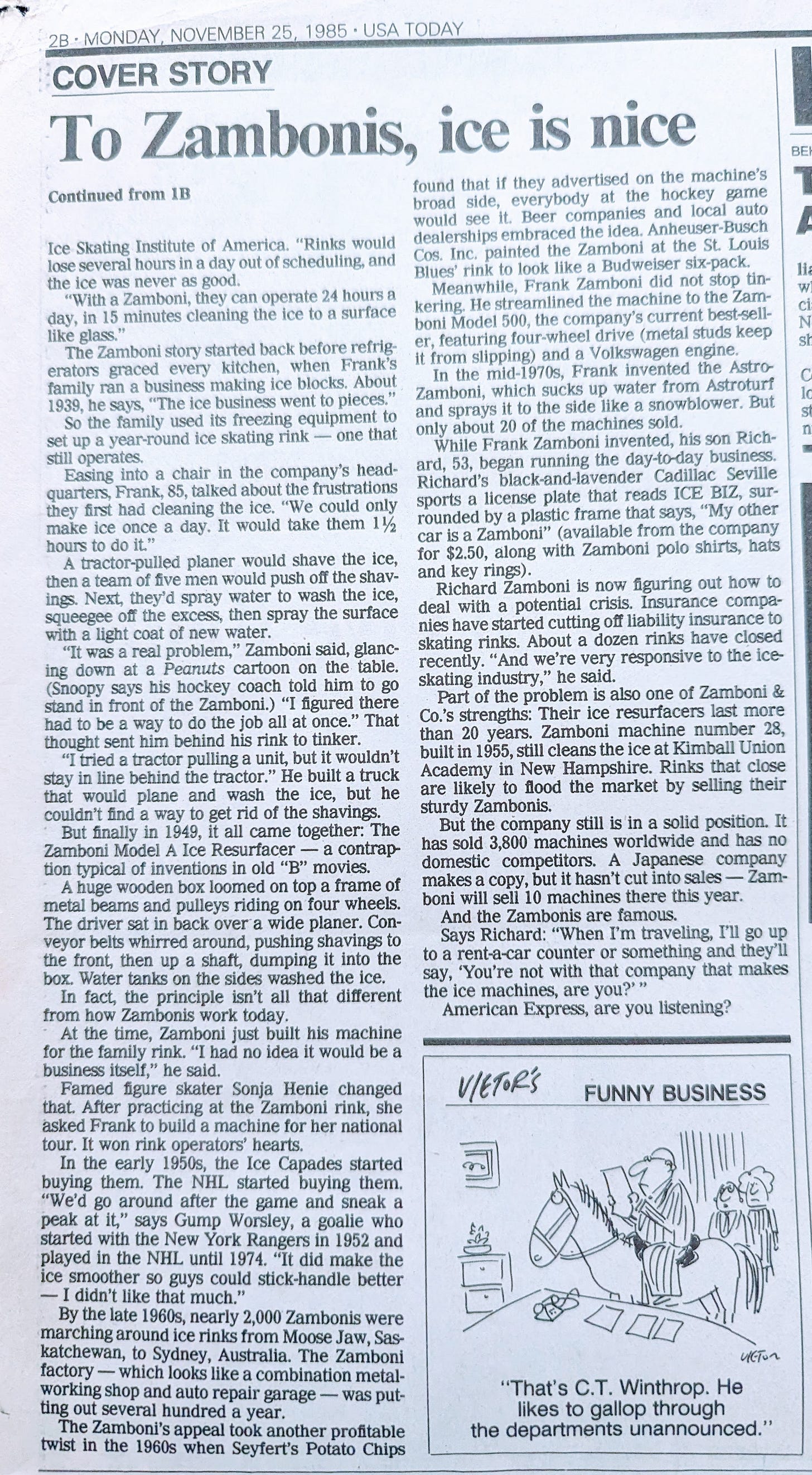

I got on a plane to Los Angeles and hung out with Frank Zamboni, 85 at the time and the actual man who invented the actual Zamboni machine. (He died in 1988.) His son, Richard, was running day to day operations, and is still chairman and president. Richard at the time drove a black-and-lavender Cadillac Seville that had a plastic frame around its license plate that said, “My other car is a Zamboni.” He gave me one of the same frames. (I put it on my Renault Alliance. Look that one up, kids.)

The Zamboni building wasn’t flashy — more like a giant auto repair shop combined with an ice rink. There had to be a rink for testing the machines, though sometimes the three-ton machines were taken for test drives on the street outside, which was a hell of a sight.

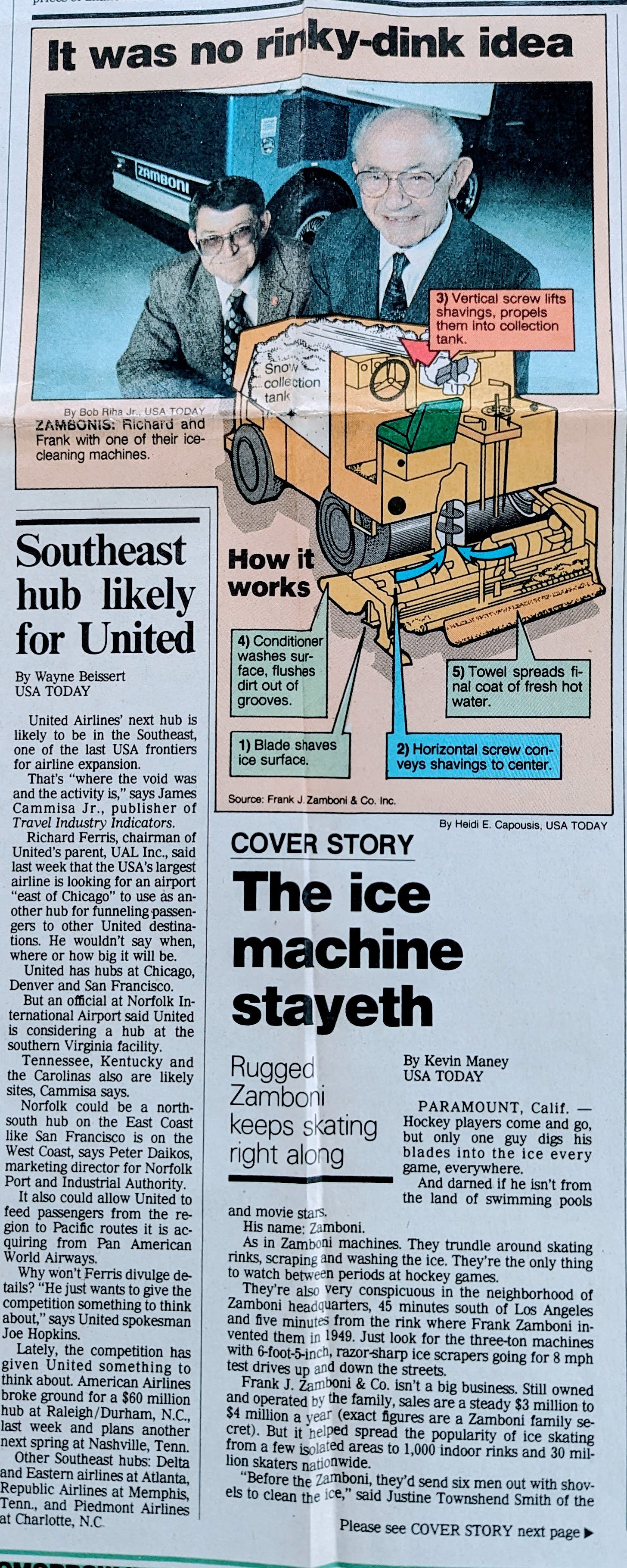

If you are reading this and have never, ever been to an ice rink, a Zamboni is the machine that drives around the ice scraping off the top layer and adding a new layer of water, making a clean sheet of ice in 10 or 15 minutes.

Now that I advise companies on category design, I’m struck by how wonderfully the Zamboni illustrates how category design works. In our practice, we tell companies to focus first on the problem to be solved, and how the context around that problem is changing — like if there are new pressures on the problem, or new technologies that could help solve the problem.

If you understand the problem and context, you’ll see the innovation and business that can be built to solve the problem. And if you do that, you’ll create a new category of product or service.

In the 1930s, before electric refrigerators became common in homes, the Zamboni family operated a business in LA making ice blocks that went into home “ice boxes” — the refrigerators of the day. But by 1939, electric refrigerators were catching on and the Zamboni ice-making business melted. The company pivoted: It used its freezing equipment to build a year-round recreational ice rink.

That’s when Frank Zamboni saw the problem. Before the Zamboni, a team of five or six guys would need some 90 minutes to clean the ice with scrapers, shovels and hoses. The long, labor-intensive resurfacing ordeal meant the rink would be non-operational for many hours a day, or people would have to skate or play hockey on snow-covered, chopped-up ice. Either choice was terrible for business.

“I figured there had to be a way to do the job all at once,” Frank Zamboni told me. That was the 1940s. There was new technology he could harness — for instance, the four-wheel-drive Jeeps that had been built for World War II. Jeep-style technology could allow a vehicle to get around an ice surface without sliding. Zamboni started tinkering. In 1949, he finished what he called the Zamboni Model A Ice Resurfacer.

It had a Jeep-like chassis. On top was a huge wooden box. The driver sat in the back over a wide planer that scraped the ice. Conveyer belts picked up the shavings and dumped them in the box. At the same time, water tanks bolted to the sides washed the ice, leaving a gleaming smooth surface in a fraction of the time and cost of manual methods.

Still, Frank Zamboni was just doing this for the family rink, solving his own problem. He thought he was going to just build one machine. “I had no idea it would be a business itself,” he told me.

But then things started happening. Famed figure skater Sonja Henie was practicing at the Zamboni’s rink and saw the machine and asked Frank to make one for her world tour. The Ice Capades started buying them, too. Then the National Hockey League caught on. One of my favorite parts of doing the story was talking to legendary NHL goalie Gump Worsley. “We’d go around after the game and sneak a peak at (the Zamboni),” he told me. “It did make the ice smoother so guys could stick-handle better — I didn’t like that much.”

By the 1960s, 2,000 Zambonis were in operation around the world. The machines made ice sports and rink ownership viable. Hockey, figure skating, speed skating and other ice activities would all barely exist if not for the Zamboni.

Frank Zamboni had created a new category of product, and for decades no other company could touch it. You know you’ve thoroughly won a category when people call even your competitors’ products by your name. Zamboni is as much a noun as a brand. (As my colleague Mike Damphousse likes to point out, these are called proprietary eponyms. Others include google, kleenex, xerox and, believe it or not, heroin — once a Bayer pharmaceutical product.)

Another way to know you’ve won a category is if you’ve created the dominant design for the whole category. That means that your version of the product or service is so thoroughly embraced that anyone else making the same thing has to make it similar to yours. Apple won the dominant design for smartphones and now all smartphones look and act much like an iPhone. In the 1980s, Chrysler created the dominant design for a new category of vehicle called the minivan, and ever since most all minivans have looked a lot like Chrysler’s.

When you win the dominant design, you become the rule-setter for the category, and the rule-setter always has an advantage over everyone else. So, while there are now a number of competitors making ice resurfaces, they all look like Zamboni’s machines. They’re expected to look like Zamboni’s machines.

Now, after 75 years, the Zamboni company is still dominating the space. The company has kept innovating. It started making electric Zambonis — you can buy one for about $160,000.

And that very first Zamboni was recently bought by the Los Angeles Kings hockey team, which will put it on display in a museum at LA Kings Iceland.

Here’s my original story as it ran on November 25, 1985, in USA Today. It’s not available online.