In 1996, Here's What We Thought the Internet Would Do To Elections

How wrong we were isn't a great sign for how we'll manage AI and politics

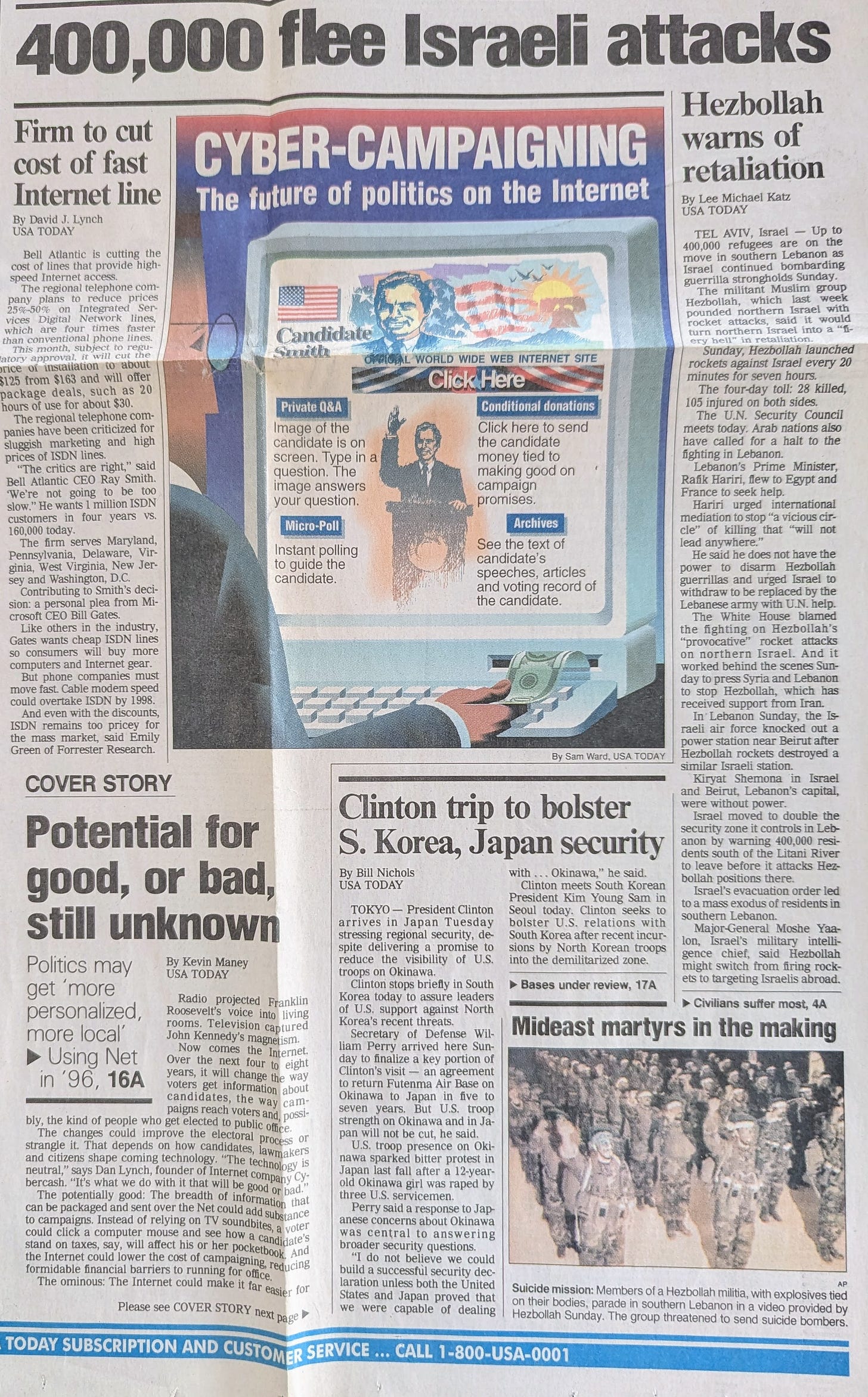

In April 1996, as the election heated up that would put Bill Clinton in the White House for a second term, I wrote a long front-page story about the emerging internet and how it might impact politics.

Here’s the most profound thing that I and most everyone I talked to back then got so wrong:

We all thought people actually wanted to think hard.

And that the internet would help them make more informed voting decisions based on issues and facts.

Ed McCracken, at the time CEO of Silicon Graphics, suggested, as I wrote, that “people may tune out news and ads until a few days before the election, then sit at a PC to sort through the candidates and issues.” Another expert foresaw something called modeling: any voter could enter some personal information on a candidate’s web site and get back specifics of how that candidate’s positions would impact that voter.

“The most obvious effect of the internet on elections will be the amount of information available to voters,” I wrote. “It could help ease one of the biggest complaints about elections: shallow media coverage that focuses on polls, conflicts and personalities.”

Yeah, glad the internet fixed that.

While there were concerns back then that the internet could create problems like making it harder to track political donations, the overall consensus was that the internet would lead to more intelligent voting. “The breadth of visual information and data available will let voters almost feel they know a candidate personally,” I wrote. I quoted David Blohm, who had created software called Vote America, as saying: “Maybe it will take us back to the 1800s, when people made speeches off the backs of trains. It will get a little more personalized, more local, more direct to the voter.”

There was a lot that was difficult to foresee in 1996. The internet then had about 20 million users in the U.S., a tiny sliver of the population. Today, 95% of the U.S. population is on the internet, or about 323 million people.

Most people in 1996 accessed the internet over a modem connected to a phone line – a slow, balky connection that made video nearly impossible. Text and static graphics loaded slowly. Digital transactions were not considered secure, which meant most people would not put credit card information into a site. Contributing to a campaign through the internet wasn’t a thing.

Strangers chatted online on “bulletin boards,” but social media didn’t exist. We didn’t even have blogs yet. The first search engines had just started to appear. No algorithms pushed content to users. Compared to the dystopian Blade Runner city we’ve turned it into, the internet in 1996 was more like a bucolic open prairie.

Sure, there were some inklings in 1996 about what might evolve. “Today, if a candidate wants to tailor a video message to a narrow group, the best he or she could do would be to buy ads on a cable TV channel such as MTV or The Golf Channel,” I wrote. “But on the internet, people join narrow niche groups. At some point, candidates will be able to craft video messages geared to such narrow niches, sending the videos over the internet to the on-line places those people visit.”

But even with that, we were naïve. The people I talked to thought those targeted messages would be about issues.

Almost all the other concerns voiced in the story were about money and politics, but in ways that didn’t really pan out. One thought was that software would allow donations to be tied to a campaign promise. People might release half a donation up front, with other half contingent on the promise being fulfilled. Turns out that was impractical (candidates just want the money up front to win) and would’ve been dangerous (governing decisions could end up being even more influenced by money than they already are).

Looking back from today’s perspective, what went wrong since 1996 is not a mystery. Social networks and digital media increasingly isolated voters in their own echo chambers, amplifying what we already want to hear and cutting out what we don’t want to hear. Creators of algorithms understood that more extreme content gets more attention, and attention in an ad-driven media equates to profits. So, we get served extreme content in our echo chambers, dividing society into us vs. them. Issues become less important than tribalism.

The early internet allowed for an anonymity that at first seemed exciting and freeing. It was in 1993 that The New Yorker published its prescient cartoon showing a dog using a computer with the caption, “On the Internet, nobody knows you’re a dog.” But anonymity allowed people to be crass, insulting assholes in ways they never would in real life. Decades later, being a crass, insulting asshole has become part of real life, and politics. Donald Trump’s rants seem normal to a segment of the population.

In a different universe, some different decisions along the way could’ve led to different outcomes. If social networks and digital media had always relied on subscriber fees for revenue instead of ads, they might’ve been more responsible about extreme content. If we had always had to be our real selves everywhere online, we might now be less tolerant of asshole-ism.

In 1996, nobody had that foresight. No one I remember talking to was having that kind of conversation. The tech industry was happy to let the internet evolve from a bucolic prairie into a barely-governed wild west.

Now here we are in 2024. The internet is old, but artificial intelligence is new. AI is about where the internet was in 1996, and no one has any idea what impact it will have on politics and elections in the decades to come.

There’s still a chance to make good decisions and get a good outcome. But if history is a guide…we don’t seem to be great at anticipating what might go wrong and proactively stopping it.

Oh, and for what it’s worth, on that same front page where my story ran, the main headline read: “400,000 flee Israeli attacks: Hezbollah warns of retaliation.”

Welcome to The Twilight Zone.

—

Here is the story as it appeared in USA Today on April 15, 1996. It isn’t available online.