I’ve been thinking about Andy Grove lately – and, if he were still around, how disappointed he’d be with the company and country he loved so much.

I also miss him.

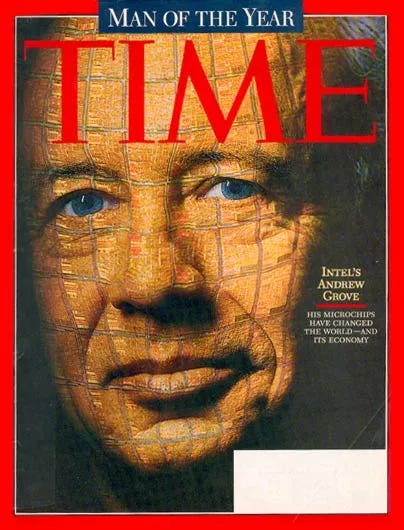

Not that long ago, Intel was one of the most important U.S. companies – and in 1999 the most valuable company on earth, the NVIDIA of its day. Intel was, quite literally, the engine underneath the early Silicon Valley-led tech ecosystem. Grove was on Intel’s co-founding team in 1968, became president in 1979, CEO in 1987, and finally retired in 2005. He published the influential business book Only the Paranoid Survive in 1996 and the next year was Time’s Man of the Year.

He was irascible, short-tempered, blunt, funny, deeply thoughtful and had a heart as big as a chip factory. I interviewed him a number of times – maybe more than any of the tech superstars of the day. He’d regularly read my columns and send one-sentence email commentaries that ranged from “This is interesting” to “This is stupid.” (Those were two actual emails.)

Intel is stumbling now. Its current CEO, Patrick Gelsinger, recently announced it is cutting 15,000 jobs – 15% of Intel’s workforce – as it restructures around a new manufacturing strategy and a push to quickly build new generations of chips to try to compete with NVIDIA and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company. The U.S., thanks to Intel, once dominated global chip manufacturing, but that momentum has shifted to Taiwan – a problem for U.S. national security.

At the same time, the U.S. is struggling to uphold ideals that Grove cherished, particularly the belief that we are a nation that is stronger and better because of immigrants and the opportunity they find here.

He and I talked about that quite a bit. Grove was born in Budapest, and his family was Jewish. When he was eight, the Nazis occupied Hungary and sent 500,000 Jews to concentration camps, including Grove’s father. His father survived and unexpectedly returned to the family after the war, emaciated and unrecognizable to Grove.

In 1956, Grove was at university in Budapest when protests broke out against Hungary’s Soviet puppet government, and Grove joined in. A couple days later, the USSR shelled the city and Soviet troops stormed in to put down the uprising. One Soviet soldier busted into the Grove house while Andy was there, took Grove’s mother into another room, and raped her. Grove decided to get out of the country, and made a harrowing escape into Austria, then made his way to New York City. He arrived not knowing English and with no money.

Grove wrote about all this in his 2001 book Swimming Across, and I interviewed him about the book, just two months after 9/11.

But Grove, having landed in America, was smart and determined. He got an engineering degree from City College of New York (CCNY), which is cheap or free and has long been devoted to helping raise up those who come from less. He moved to California and in 1963 got his Ph.D. in chemical engineering from Berkeley. Five years later, Grove helped start Intel with Robert Noyce and Gordon Moore.

Immigration and CCNY were topics when I last saw him, in 2006.

He’d retired a year before, and I’d sent him a note asking what he’d been up to with all his free time. He invited me to come by the office he’d set up for his newly-formed Grove Foundation, in Los Altos, Calif. I wrote a story about it for USA Today. It starts out this way:

Andy Grove flips open a large pad on an easel to show me 11 handwritten note cards, which he taped in a formation. It's as charming and homegrown as a third-grade project. And it's meant to explain the home stretch of Grove's life.

So we're meeting at the foundation, which employs five people in an office so unremarkable it could be in the back of a small-town car dealership. Grove is wearing a light blue golf shirt and olive khakis, the BlackBerry on his belt buzzing constantly. His mood is up, his attitude at times mischievous, and he gives off the kind of lightness that comes from shedding boulders of responsibility and a schedule as tightly packed as transistors on a Pentium.

"I've given a great deal of thought to your question," Grove says, turning to the cards on the pad. I had asked to come by and talk about his retirement. That prompted Grove, for the first time, to think about all the things he's been doing in the past year and find a theme. On each card he wrote an area of interest or activity — "immigration," "City College of New York" — and moved them around with the help of his wife, Eva, until the cards' relationships made sense.

"What the foundation is really about," Grove says, "is to strengthen, regain and protect the America I came to."

At the time, there was an anti-immigration bill being debated in Congress. Grove lobbied against it and wrote opinion pieces that denounced it. He said if it wasn’t for CCNY, he’s not sure how he would’ve gotten a college education. To make sure new immigrants have that same chance, Grove gave the college $26 million.

He had another beef, which he’d only find worse today. As I wrote:

In general, he wants to do what he can to prevent religion from playing a role in scientific and medical research — as it did, Grove believes, in the U.S. government's decision to limit embryonic stem-cell research. "Respect for what science means is eroding," he says. "When people have strong beliefs, they confuse assertions with facts. Science is a respect for observation and facts in the face of beliefs."

See what I mean? He’d be horrified if he was still around, and no doubt pulling whatever levers he could to push back.

He’d be equally disgusted by Victor Orban’s autocratic rule in Hungary, especially Orban’s relationship with Russia’s Vladimir Putin. Grove had never returned to the country of his birth. “I didn’t like my life in Hungary,” he told me. “It would be like picking at scabs.”

About a year after our meeting, I left USA Today to join a Conde Nast magazine. For my last column, after writing it for about 15 years, I emailed a bunch of tech leaders I’d engaged with and asked if they wanted to get in any last shots. Grove wrote back in about two minutes. It was classic Andy:

“You almost got me lynched when you quoted, for reasons incomprehensible to me to this day(!), my comment likening PR people to Oompah Loompas. The only reason I’m alive is you were kind enough to stick it in a blog, which nobody reads.”

I had to return volley. At the end of that column, I wrote: “And, finally, to Andy Grove: I quoted you saying that because it was really stinkin’ funny. And now it’s in a column, which, apparently, a lot of people did read.”

By that time, Grove was showing signs of Parkinson’s. He died in 2016. The Computer History Museum held a memorial tribute to him, and I was touched that his colleagues and family wanted me to be there. Of course, I attended.

As I said, I miss him.

—

The story about our last meeting is in the link above. My story about his book “Swimming Across” is below. It originally ran in USA Today and then went out on the wires. This is as it appeared in the Home News Tribune in New Jersey.

legendary post... again Kev

Brilliant. Thanks for this. I never met Andy but have had the privilege of working with many leaders that he helped create and inspire. As you may recall, my first gig after returning from my own Hungarian story was at EMC. Dick "The E" Egan was still the chairman at the time, having founded the company after working for Andy. When I met Dick during my very first week as the company's new entry-level PR specialist (EMC was still that small) and he heard about me teaching in Hungary, EMC's founder immediately brought up his old mentor, Andy Grove. Years later Andy's former PR person Pam P, who, knowing Pam, I'm guessing was the one that didn't appreciate the Oompah Loompa reference and threatened a lynching, hired me into Autodesk. These two, yourself, and so many more have shared such wonderful stories about Mr. Grove. The world does indeed need leaders like him right now. More than ever. Thanks again Kevin.