Data Center In a Beer Can?

My intersection with the long, weird journey of quantum computing

In July 1999, I opened a story for USA Today like this:

“Around 2030 or so, the computer on your desk might be filled with liquid instead of transistors or chips. It would be a quantum computer. It wouldn’t operate on anything so mundane as physical laws. It would employ quantum mechanics, which quickly gets into things such as teleportation and alternate universes and is, by all accounts, the weirdest stuff known to man.”

Fast-forward to June 10 of this year. One news story began: “IBM shares hit an all-time high Tuesday as the company showcased what it called a ‘viable path’ to building the world’s first large-scale, ‘fault-tolerant’ quantum computer by the end of the decade.”

So, yeah! Quantum computing by 2030! Nailed it!

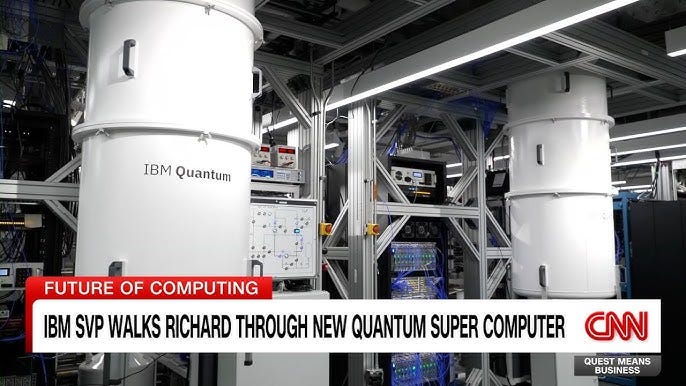

Though not exactly on your desk. The IBM machine looks more like a cross between a data room and a moonshine still, and might not fit in my Manhattan apartment. But apparently we’re getting there.

And to be fair, in 1999, the year 2030 was so far away that it seemed like we’d be living like the Jetsons by then.

I actually first heard about quantum computing from IBM. In the 1990s and 2000s, one of my favorite things to do as a journalist was spend a day at IBM Research in Yorktown Heights, N.Y., bopping from scientist to scientist and learning about all the crazy shit they were working on.

Some of those visits took me to the lab of Charles Bennett, who would regularly blow up my brain by telling me things like why teleportation will really work. (Bennett, btw, is in his 80s and still a Research Fellow at IBM.) On a 1999 visit, he told me about the emerging concept of quantum computing. Here’s a distillation of that conversation that I put in my story:

“On the theory side, quantum mechanics delves deep into areas that are nearly unthinkable. For instance, it’s possible that a quantum computer holds an infinite number of right answers for an infinite number of parallel universes. It just happens to give you the right answer for the universe you happen to be in at the time. ‘It takes a great deal of courage to accept these things,’ says Charles Bennett of IBM, one of the best-known quantum computing scientists. ‘If you do, you have to believe in a lot of other strange things.’”

Another IBM scientist, Isaac Chuang, at the time was working with well-known MIT physicist Neil Gershenfeld on building one of the first baby-step quantum computers. The key to quantum computing – a quantum computer’s version of a transistor – is the qubit. Cheung and Gershenfeld had recently built a three qubit computer.

A qubit is an atom that’s been put into a superposition, meaning that it’s both “on” and “off” at the same time. That’s like someone saying yes and no at the same time, and whether you get an answer of yes or no depends on the universe you’re in. You might get a yes, but the version of you in a different universe gets a no. The superposition is why quantum computers can calculate vast amounts of information at once, instead of sequentially like traditional computers do. They’re calculating all the possible answers at the same time.

Compare that to today’s AI, which relies on vast seas of chips in huge data centers. Each of those sequentially-calculating chips has to coordinate and work on a question in parallel with boatloads of other chips to get the fast answers you expect. So it takes hundreds of thousands of chips.

Theoretically, you could get the same speedy result by using a quantum computer the size of a beer can.

In 1999, moving from just three qubits to four qubits was a giant challenge that lots of scientists all over the world were working on. We’ve come a long way. The Starling quantum computer IBM says it will deliver in 2029 will use 200 qubits.

Think even 200 qubits doesn’t sound like much? Says IBM: “Representing the computational state of IBM Starling would require the memory of more than a quindecillion of the world's most powerful supercomputers.”

I asked Claude AI how to imagine the number “quindecillion.” It informed me that it is close to the total number of atoms in our planet.

In short, quantum computers will give us computing power we can’t even imagine, in a package that will seem microscopic compared to the expansive data centers now being built to run AI. (In about 20 years, what are the odds that those data centers will become like today’s abandoned old shopping malls?)

Of course, IBM isn’t the only company working on quantum computers. In 1999, I talked to scientists at Hewlett-Packard who were working on one. So was a scientist at AT&T’s Bell Labs. The federal government funded quantum computing research at Lawrence Livermore Labs.

These days, Microsoft, Google, Amazon and D-Wave Systems (one of the first quantum computing startups) are in the game. So are a bunch of other startups, such as Rigetti Computing and IonQ. Venture capital investment in quantum computing companies has quadrupled since 2020.

The science is proven. The technology to make quantum computing practical is emerging. These things are coming. So if not by 2030, then maybe by 2040 I’ll have a liquidy quantum computer sloshing around on my desk.

—

This is the story as it ran in USA Today on July 14, 1999, as accessed on Newspapers.com.